My fondness for beavers stems from a scene in C.S. Lewis’ children’s book, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Mr. and Mrs. Beaver bring the four children heroes to their snug house on their dam on a frozen stream.

While preparing for the action ahead, they eat a meal of freshly caught fish and boiled potatoes with butter. And tea, of course. Like Lewis, the magical land of Narnia was very English. Though all the characters have much more striking adventures for the rest of the book, I’ve always remembered that cozy scene.

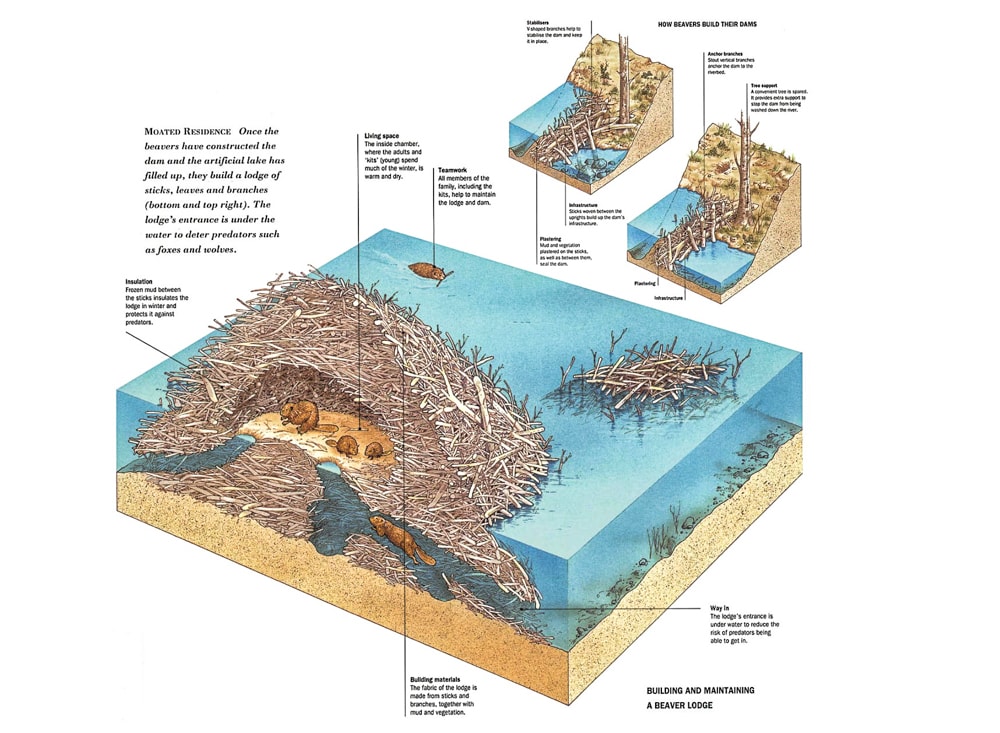

Even knowing as little as I knew about actual beavers, I understood the reality was much damper than that. Beavers build their dams with branches, twigs, and mud, reinforced with rocks, to withstand the strength of the water they hold back. The entrances to their lodges are underwater to protect them from predators like wolves, bears, coyotes, even intrepid hawks.

Despite having plenty on hand, they don’t eat fish, though they might like the potatoes. As herbivores, they eat the sweet cambium layer right under tree bark, ferns, grasses, twigs, tubers of water lilies, and other available plants.

Before the fur trade spread in the early 1600s, the North American continent was one mesh of wetlands after another. This was thanks to at least 7.3 million years of landscape management by hundreds of millions of beavers. Their dams created ponds and channeled streams and rivers. They dug canals, bringing water into the surrounding land. Holding it in the water table, encouraging deep root formation in the surrounding plants. They built lodges on or near their dams.

Underwater burrows in the sides of the stream provided safety from predators, winter protection, and a place to raise young. Family groups building offshoot dams, canals, and lodges created vast beaver-friendly, wetland habitats. Earth’s consummate water engineers, they had it all figured out.

The fur trade decimated them. It didn’t peter out until the end of the 1800s, when there were almost no beavers left. In the meantime, North American land was being claimed by people who wanted to farm or range cattle. Beavers were not welcome in such places. You can understand why when you see the felled tree below. Owning an orchard or trying to put up fence posts while neighboring a beaver was problematic. So beavers continued to be hunted and killed.

To stem this, wildlife rehabilitators began to capture and relocate them. Both to save the species and to reestablish beaver habitat for water management. Getting them into the wild and inducing them to stay there proved to be interesting challenges. In his engaging book, Eager, journalist Ben Goldfarb recounts the post-World War II attempts in western states to get beavers deep into the wilderness.

One approach was to drop them, in pairs, in specially designed cases that would parachute down and open on landing. It worked better than you’d think it would. But making sure the two beavers were interested in each other and then flying them off was cumbersome. The project was soon abandoned for more pedestrian trucking.

A few years ago, I was hiking in southeastern Washington on a trail that began along extensive wetlands. Once I saw the tree below, I knew I was in beaver territory. The marks of their ever-growing, self-sharpening teeth, fortified with iron (which colors them orange) are unmistakable.

An inveterate reader of information placards, I discovered the wetlands had been, until recently, ranch land. Beavers had been introduced to recreate the wetlands that had once been there.

Higher up, the trail I was hiking runs along Liberty Creek. Behind me, out of sight, was Liberty Lake. By severing the healthy connection between the two, human intervention led to the degradation of the lake. Instead of a proposed million-dollar wetland restoration project, beavers did the work for free.

It wasn’t, as one Spokane journalist noted, “all peeled cambiums and roses.” Parts of the original trails flooded periodically. But instead of scrapping the project, the Spokane County Parks Department got together with trail groups and rerouted the trails.

Goldfarb found this attitude to be widespread in Washington. Environmental groups, government agencies, and Native Americans are joining forces. Making Washington, he wrote, “the country’s most sizzling hotbed of castor relocation.”

Castor canadensis, our North American beavers, like wolves, prairie dogs, and plains bison, are a keystone species. They are the dominant force in creating and maintaining the ecosystems they are associated with. By partially blocking rivers and streams, beavers create larger riparian areas, allowing water to pool into wetlands, water meadows, and wet forests.

Wetlands are prime habitat for many species of amphibians, fish, reptiles, insects, birds, and mammals. A slower river means less erosion. Water pooled in one place means more is soaking into the surrounding ground.

When we think of climate change solutions, we think about electric cars, windmills, solar panels, the Amazon rainforest. All important. More amorphous challenges like land degradation because of farming and ranching practices, soil erosion, and ecosystem loss draw little public attention. But the realization that beavers are allies in this work is spreading.

Recent findings have helped. After the devastating wildfires the west has endured, researchers discovered that areas of beaver habitat survived. These green oases allowed space for safety and recovery for wildlife. Ponds and slowly moving water allow sediment to settle on the bottom. Thus, downstream from the filtering action of beaver dams, rivers choked with ash ran clean.

The dams have proved so valuable in managing water movement and quality that, lacking beavers, structures called beaver dam analogs mimic them. They have the advantage of going where they are needed. The answer for times that leaving it to beavers can mean tree removal and flooding where you least want them. But, without the constant tending and reinforcing beavers give their dams, the structures eventually give way under the push of water.

This underscores something important: everything in nature is an interrelated system. We can’t ever fully replicate what beavers do because they mean too many things to the habitat they create. We can build dams and filter water. Work to restore waterways and recreate wetlands. There are organizations worldwide preserving wildlife of all kinds.

But beavers juggle all of this by themselves, and at a scale the environment can manage. It’s their evolutionary destiny. Recognizing that we mere humans don’t have these all-encompassing talents, California’s Department of Fish and Wildlife created a beaver restoration unit last year. A huge change from their prior stance of treating beavers as a nuisance. The program is designed to both restore beavers to the landscape and to help landowners flummoxed by their toothy neighbors.

Widespread comfortable coexistence among humans and beavers is still in the future, if ever. Even in Washington state’s hotbed of restoration, many more are killed each year than are relocated. Like the wolves reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park, wild animals don’t recognize the boundaries we would like to set around them.

Bison cross roads and slow traffic. Wolves prey on domestic range animals. Bears show up in residential areas. Beavers love to dam the handy culverts that produce so much running water for them, thus flooding roads. It takes time and patience to find ways around these inconveniences, and humans are not noted for patience.

Wildlife needs land. And not only a preserve here and a park there, as crucial as those are. Animals need connected land to roam and migrate, to move from nesting areas to foraging areas. To find new environments as climate disruption alters their home ranges. They need to be with the species of plants and animals they evolved with.

Biologist E.O. Wilson established the Half-Earth Project, calling on the world to set aside half the planet to save biodiversity. This is doable as far as available land goes.

But prime areas for conservation, such as the Amazon and Congo basins, include multiple countries, millions of people, and are sought-after targets for corporations. Stakeholders — that’s all of us — are being asked to examine our way of life, of doing business, of thinking about our place in the world.

Earth is blessed to have groups and organizations that work tirelessly to create consensus, a slow and never-ending process. One with no simple answers or paths. Of course, we want wildlife to prosper.

So what do we need to do to create a world safe for the millions of species we share the planet with? What are we open to changing as individuals, as businesses, as communities ranging from local neighborhoods to sovereign nations?

How do we insure, as the Ecuadoran constitution puts it, that “Nature…has the right to exist, persist, and maintain and regenerate its vital cycles, structure, functions and its evolutionary processes.” We all want a world that emerges from such a vision. Designing it is not only our biggest challenge but also a task of enormous creative potential and excitement.

~ RELATED POSTS ~

Imagine a river taking her case to court. Arriving in her smooth, flowing robes, reflecting the blue of the sky, a shimmering train brushing the floor as she walks. Her tone holds great authority. It would be impossible to ignore what she says. And we all know exactly what she would say…

The American myth that the land “discovered” in 1492 was an untouched wilderness has it all wrong. It had been carefully tended for millennia. Not by wresting it from its productive ecosystems, but by fostering the bounty of the ecosystems themselves.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF HOPE: SAVING HALF THE EARTH

Biologist E.O. Wilson had a radical proposal: save half the earth to stem the drastic rate of current extinctions. The plan is both wonderfully simple and wildly complicated. It also invites us to rethink what we do with the other half.

BIOMIMICRY: DESIGNING WITH NATURE’S 3.8 BILLION YEARS OF RESEARCH

The kingfisher’s eyelid grabbed me. A dam’s changing water levels caused erosion. Designers asked nature how she would solve the problem. Her answer? Spider webbing and a diving bird’s third eyelid. Nature has been at this a long time and has surrounded us with geniuses.

You are an amazing being Betsey. I so very much enjoy your photography and writing. I hope you are very well!

Thank you so much, Aliza. All is well and I’m so happy to hear from you.

What a wonderful, powerful, and inspiring post! And if I loved that beaver picture any more than I do I’d have to be my own screaming mosh pit…