This was a year measured, in part, by the interconnections of flowing water. At the beginning, in Reweaving a River, I described a trip to an area of the Klamath River in northern California that was due to have four dams removed. One of the connections is my own: two of the dams were built with the help of my engineer grandfather. In family lore, they were his great achievement.

But they were an inestimable loss to the Yurok, Karuk, and other tribes in the area. And to the river. The water was degraded, salmon was dwindling to local extinction. A millennia-old culture was being threatened. When we constrain the vast repository of interconnectivity we call nature, we lose life itself.

Rivers are not extensions of hydroelectric plants. They are “fish, amphibians, and insects. They are eagles and ospreys. The snow from high mountains meeting the salt of the sea. They are clouds rising and falling. The land flanking their shores. The plants that grow there, fed by the nutrients of decaying fish dropped by bears and wolves; DNA of salmon blending with the DNA of pine trees.” They are the culture and lifeblood of the peoples who have lived on their shores for millennia.

When I made the trip, the dams were being prepared for demolition. So after writing the essay I waited. I went to the opposite end of the state, returning to the Anza Borrego Desert for the first time since the pandemic. I updated an early essay about my slowly developing love of the cactus family in Cactus Lingerie. I’d always found them fascinating as ecological adaptations, but stiff and ungainly.

Then I went to the desert for the first time, where they both belong to and define the landscape. There, in the interconnections with sand, rock, spindly, dark-leaved creosote, and spiny ocotillo, cacti made sense. One spring visit, I was startled into loving them by their flowers, “so lovely, so delicate, so translucent that you can’t believe your eyes. It’s as if your tough-talking, cigarette-dragging, hard-as-nails but intriguing neighbor answered the door in the softest, silkiest lingerie.”

It was another celebration of the genius of place. “It’s this mingling of adaptations of color, size, shape, and functions that connect plants to place. That gives them a sense of belonging to the landscape, to the texture and color of the air, the life of that soil, and their fellow creatures. It’s not just about the way they look, although I have learned to love that part. It’s the way they feel, connected to the magic and mystery of the powers that created them. A direct connection to the soul of the earth.”

Seeking that connection in other ways led me to contemplate something close to my heart: how do we design our world to increase well-being? How do we re-green our built environment? No one wants to live in places shorn of nature, though we all too often let it happen.

In Designing for Happiness, I described my addiction to a particular forest, how my spirits soar the minute I start walking the trail. “There is a lot of science behind this pleasant idea, along with six million years of evolution.” Study after study proves the enormous benefits of green spaces to our health, intelligence, social interactions, joy. ”We evolved to be among green, growing things. To take our cues from clouds, animals, plants, soil, rocks, rain, wind.”

We are not designed for the asphalt and cement world we’ve built up around us. “The challenge is expanding our sights beyond what we have been willing to accept as normal. There are a lot of problems we can’t solve in the short term. But this is one of the easier ones. Once we have the vision and the will to follow through, it just takes shovels.”

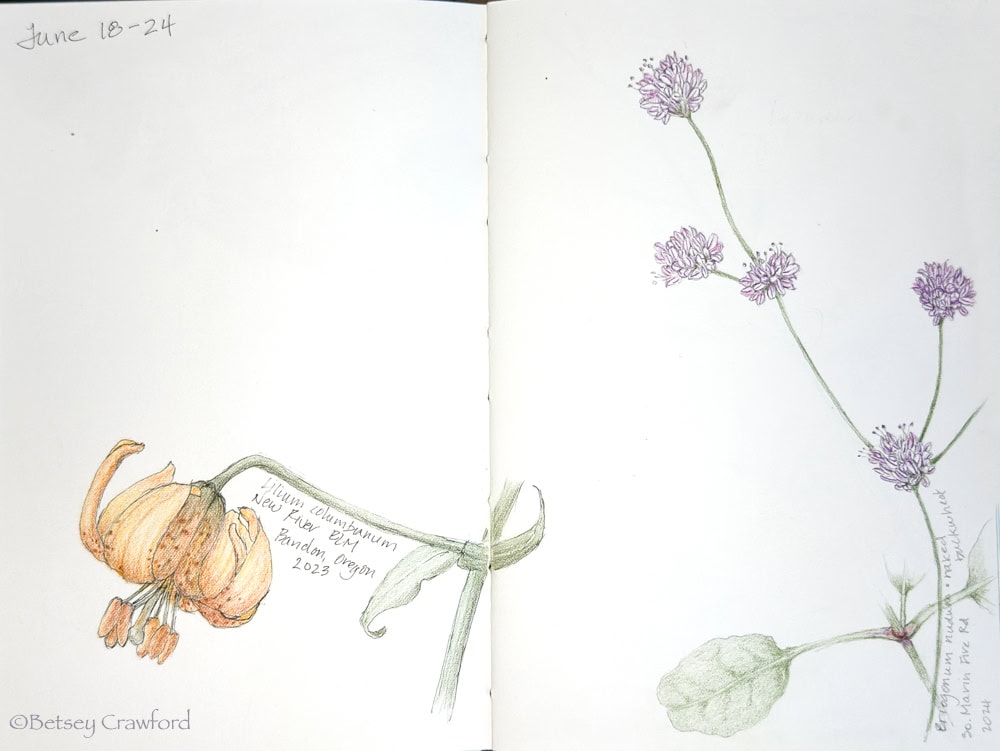

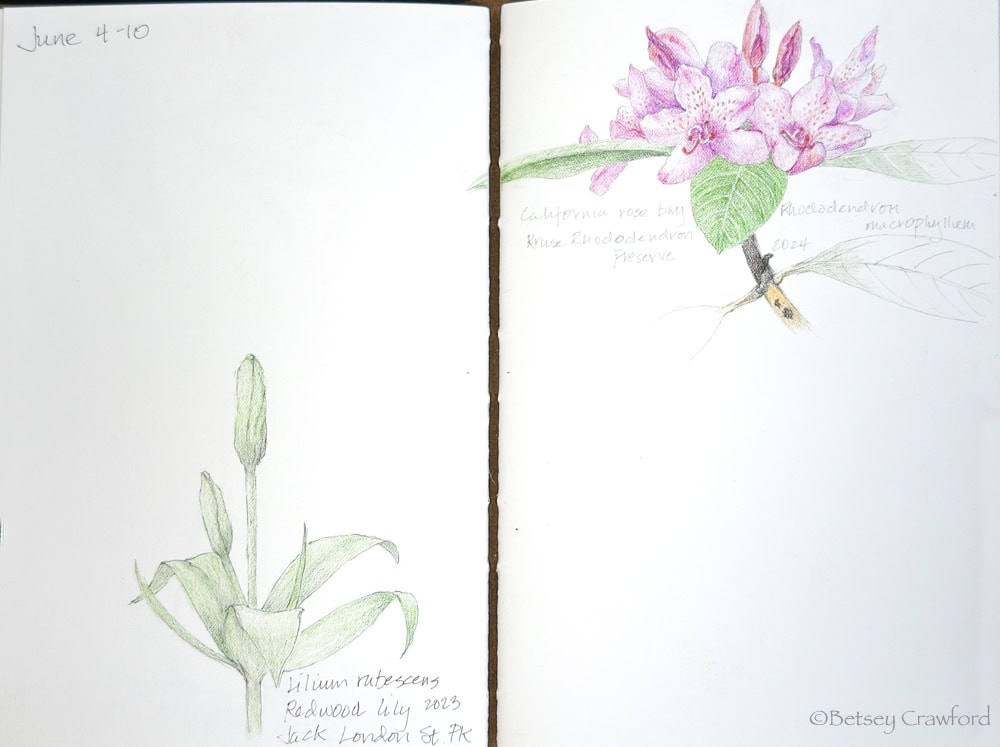

From the grandeur of re-greening the entire built world, I turned to celebrating on the smallest scale: drawing what I find in nature. In Drawing Closer to Nature, I described taking a blank artist’s journal and dating 52 spreads. Then, each week I draw something I find on hikes. The next year I return to that week’s pages and draw something else.

Photography and drawing share traits, principally that they render our vision into two-dimensional forms. “But the biggest difference, to me, is that drawing brings you even closer to the nature of the being you are seeing. With pencil in hand, I am not just seeing how a leaf or a petal folds. I’m making that same fold with my fingers. I’m participating directly in shapes, lines, mysteries. It’s not that I don’t see those things when I’m taking a photo. But I can leave the capturing of details to the camera. A drawing comes through my body.”

“The perpetual journal is an exploration into the heart of the green world, a continuing meditation on detail, surprise, joy, discovery. On nature itself, on my journey through the year, on the intricacies and beauties that our gorgeous Earth showers on us.”

In August, channels were dug through the two remaining dams. The last forty miles of the Klamath River could run free to the Pacific Ocean for the first time in over 100 years. Next was the final demolition and then the big question: would the salmon come back?

For September’s Season of Creation, I went back to celebrating on a large scale. I paired poetry and prose with images of trees in The Majesty of Trees. “Trees are among the most powerful beings on the planet. Solid and magnificent, they cover and hold together a third of Earth’s surface. Their cooling, oxygen-laden breath ensures the existence of the rest of life. They are full of magic and mystery. They exert their power both spiritually and literally….” No culture that lives with trees has not revered them.

I continued exploring trees in Tiny Forests, Big Miracles, about the worldwide phenomenon of planting forests the size of an average backyard. Native trees, shrubs, and understory plants like ferns are planted densely to stimulate competition and fast growth. The result is a functioning forest in 10 years, and a mature one in 30-50 instead of the century or two it can take a natural forest to fully mature.

After the first few years, “Plants go through their life cycle, dropping their seeds, are replaced by new growth as they die back. Insects, birds, and small mammals flock to it. Soil grows richer and more complex. Carbon is sequestered and pollution is reduced. Water is held in the ground. Each geographical area produces its own dynamics that play out over time.” Built-up areas that can’t give space or time to natural forests can nevertheless reap some of their many benefits.

In October, just weeks after the demolition of the final dam. salmon were found far upstream in the Klamath River basin. They were able to get to cold water streams for spawning for the first time in generations. “Our salmon have returned home,” Joseph L. James, chairman of the Yurok Tribe said. “It’s a beautiful thing.”

Needing to find consolation in November, I turned to Blessed Unrest: Sowing Seeds into the Whirlwind. It was first written eight years ago. I rewrote it as we once again discovered that progress toward a sustainable and just future is not remotely linear. That evolution is often bewilderingly and heartbreakingly tortuous.

Yet, in the face of all our challenges, there are hundreds of thousands of organizations and millions of people taking action worldwide. They are the Blessed Unrest, as environmentalist Paul Hawken calls them in his book of that title. Working for the health of rivers, streams, and wetlands, for clean air, for better public transportation. Championing Indigenous rights, workers’ rights, civil rights, the right of girls worldwide to an education. Concentrating on land, farming, hunger, and housing. There are endless interconnections; each issue is woven into all the others.

This last point is at the heart of everything. Interconnectivity is the most important dynamic on Earth. Our breath depends on trees. Trees depend on mycelium at their feet. Mycelium depends on sugars that green leaves form from sunlight. Those sugars in various configurations feed all other living beings on the planet. Bears. wolves, and eagles feed on salmon. The discarded bones fertilize the forest. All living beings need space, peace, nourishment, clean air, rivers that run free.

In The Majesty of Trees, I included a quote from David Haskell’s “The Song of Trees” that sums up a year of connections beautifully. And sends us forward. He speaks of listening to trees but I’m sure he would agree that it’s listening to all of Nature. From her, we will only ever receive the message that we are deeply and powerfully connected to everything.

We’re all — trees, humans, insects, birds, bacteria — pluralities. Life is embodied network….

Our ethic must therefore be one of belonging, an imperative made all the more urgent by the many ways that human actions are fraying, rewiring, and severing biological networks worldwide. To listen to trees is therefore to learn how to inhabit the relationships that give life its source, substance, and beauty.

May we all treasure and further our deep interconnections in this new year.

Top photo: the Klamath River held in place by the Iron Gate dam, the most westerly and last to come down.

~ RELATED POSTS ~

Imagine a river taking her case to court. Arriving in her smooth, flowing robes, reflecting the blue of the sky, a shimmering train brushing the floor as she walks. Her tone holds great authority. It would be impossible to ignore what she says. And we all know exactly what she would say…

BORN TO RELATE: THE POWER OF SYNERGY

The cosmos was born to relate. For 13.8 billion years, nothing has endured without a relationship. Optimistic and exuberant, synergy is the continual birth of new realities from the collaboration of disparate ones.

The pandemic showed us that our culture has its values and rewards upside down. Tug on any one string, and you pull on the whole fabric. Tug enough strings and the fabric loses all integrity. We are all completely, intimately, and sometimes desperately interrelated.