Half Earth is different. It is a goal. People understand and prefer goals.

~ E. O. Wilson ~

On spring mornings thirty years ago I woke to a dawn chorus of birdsong so loud and rambunctious and beautiful that it filled me with joy every day. The birds had a lot to say as they flew by my windows, building nests, feeding young, fending off whatever they took to be threats.

Some simply perched on branches and sang the day into existence. In late May martins, the largest of blue-black swallows, would join the choir. They filled my martin house and spent their days nabbing mosquitos as they swooped over the meadow and the marsh.

When I left in 2011, the thrilling symphony had already vanished. One spring the martins didn’t come back. The number of songbirds dwindled year by year. There were still birds, especially crows and bluejays. I love their cheekiness and brilliance. But their increasing presence was a sign that the songbirds had largely abandoned the area to them.

Nothing about the surrounding area had changed. The same houses flanked mine, the protected land behind remained wide open. There were acres of trees and shrubs for nests and cover. But the birds’ winter homes in Central and South America were dwindling.

Along the Atlantic flyway that supported their migration, more and more wetlands were being filled in. Trees felled for houses. Meadows paved for parking lots and malls. Gardens filled with exotic plants that didn’t provide the food the birds had evolved with.

The same story can be told about many species: wolves, bears, salamanders, owls, frogs, butterflies. The list is long and sad. Biodiversity needs space and lots of it. Animals need room to roam and migrate. All species need large areas of the world still filled with the plants that have nourished them for eons.

They need habitat that provides the shelter they look for. Without room to meet their evolutionary and biological needs, species dwindle in numbers. Isolated, smaller populations court extinction. The disappearance of species destroys ecosystems. Our shared planet, entirely made up of ecosystems, degrades. Voices and visions Earth will never encounter again vanish.

Biologist E.O. Wilson has a radical proposal: save half the planet. That’s what’s needed to stem the drastic rate of current extinctions and to provide enough room to preserve the earth’s biodiversity. His Half-Earth Project, “with science at its core and our transcendent moral obligation to the rest of life at its heart…is working to conserve half the land and sea to safeguard the bulk of biodiversity, including ourselves.”

In one sense, the proposal is wonderfully simple. There are still vast reaches of northern boreal forests, tropical rainforests, oceans, coastal mangroves, coral reefs, and mountain ranges. It seems you could handily find half the earth to save. But, of course, it’s much more complex. In the first place, although every country on the globe has set aside preserves, only 15% of the earth’s land surface and 5% of the ocean is already protected.

A third of those preserves are under pressure from human activities, often sanctioned by the same government that supposedly protected them. Some countries contain areas of more biodiversity than others. In asking them to protect a higher percentage of their land for the good of all, other nations would need to consider compensation.

A profound complication is that we don’t know that much about the beings we share the earth with. Wilson points out that we’ve only identified and named about 2 million species. Of those, a handful have been studied in depth. The fungus crowd advises us to expect 5 million fungal species alone. Estimates for the total species on earth — bugs, bacteria, fungus, lichen, plants, animals — range as high as 100 million.

We discover new species all the time. Given the current rate of extinction, we can assume many are blinking out before we ever know them. The International Union of Conservation of Nature has assessed a mere 96,500 species. Of those, over 27,000 are on their Red List of species threatened with extinction.

Knowing our neighbors and where they live will help us decide which areas to save. Yet, despite out growing need for knowledge, on-the-ground biological studies are losing students and funding. Thus, our understanding of ecosystems, a science under a century old, is limited.

We are badly in need of experts in the natural sciences, Wilson says. Their numbers are shrinking in relation to technology and engineering. We are abandoning the wider living environment in favor of the human environment.

Despite political and educational inertia, there are groups and places that are moving forward. Wilson expressed guarded optimism in a 2016 interview on the publication of his book, Half-Earth. We can build, he said, on what is already in good shape. Much of the rainforest in the Amazon, the Congo Basin, and New Guinea. Grasslands in the Serengeti and South America’s El Cerrado.

South Africa is an especially diverse area. Wilson compares the enormous and teeming Lake Baikal in Siberia to the Galapagos. They are both sanctuaries for diversity and cradles of evolution. Every area of the world still has ecosystems, sometimes vast, that are functioning well.

We can also connect land already preserved, a vital step. Preserves separated by roads, industry, or private property prevent animals from migrating to their accustomed places. Or to new areas if climate disruption means their traditional homelands can no longer sustain them. Even cutting a small dirt road through a preserve can mean the introduction of non-native plants. With no natural controls and rapid life spans, they can displace native plants and wreak havoc quickly.

On Wilson’s list of the most important places to protect is such a corridor: the pine and oak forests extending through the US southwest into the Cordilleras of Central America. This ancient ecosystem is home to a quarter of Mexico’s native plants and winter quarters for the monarch butterfly.

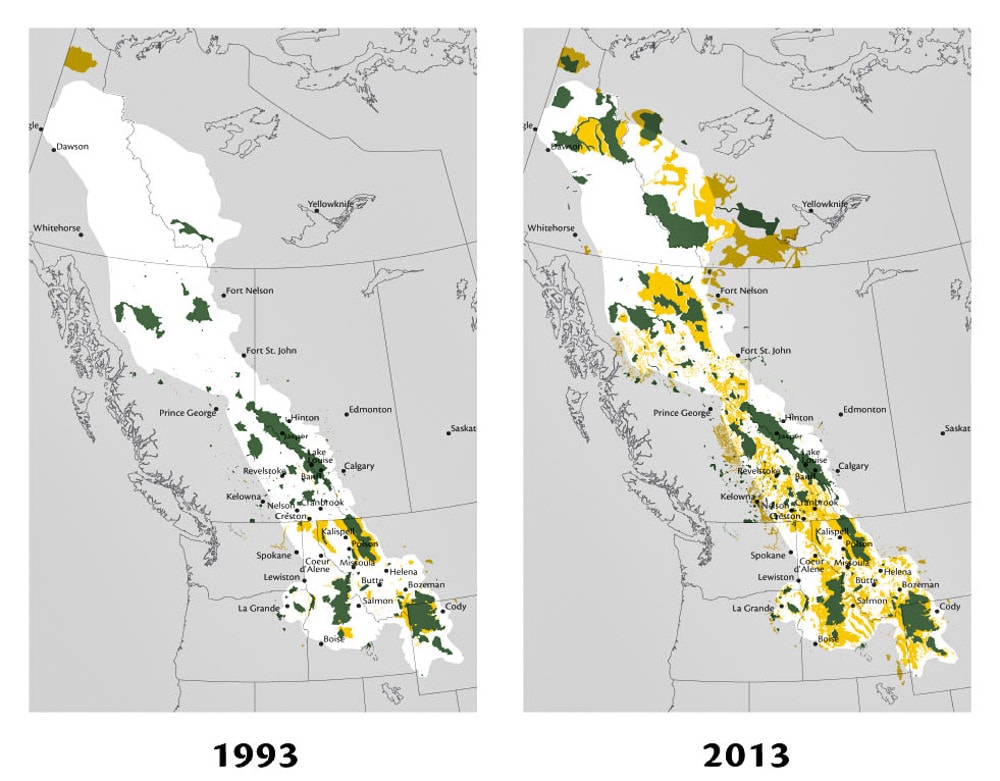

The Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative is working on a corridor from Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming northward along the Rocky Mountains. It ends in the vast Peel watershed in the Yukon. Along this 2,000-mile stretch, there are many magnificent national parks and wildlands. Connecting them will protect one of the last intact mountain ecosystems in the world.

The maps below show the progress, in yellow, in Y2Y’s first twenty years. The landscape photos accompanying this post are all from this corridor.

To indicate what it takes to manage such a feat, Y2Y, starting in 1993, has enlisted over 300 partners. These include Native American groups, conservation organizations, landowners, mining and lumber companies, government agencies in both the US and Canada, and donors.

The organizers recognize that land preservation has to work for as many of the stakeholders as possible. Ways have to be found to work with ranchers so the burgeoning number of grizzlies in a preserve isn’t a growing threat to calves. A major mining company agreed to spend 19 million dollars on land to augment the Y2Y corridor. Land planners are brought into the circle to provide wildlife with ways to cross roads and migrate through settled valleys. Convincing a developer to set aside an extra 300 feet can make or break a usable wildlife corridor.

So, it’s complicated. All that negotiating and planning by one group, operating in one area of the world. But it’s doable. Such groups are on the ground and tireless. California — a state closing in on 40 million inhabitants, with the world’s fifth largest economy — has protected half its land. There are fifteen national parks and recreation areas. The Anza Borrego Desert State Park is the largest state park in the country and one of 300 in the state.

Towns of every size actively acquire open space for preserves and parks. An hour north of me a cross-state corridor is being created to connect protected land in the Coast Mountain Range. The California Native Plant Society is a political and environmental powerhouse. But it’s a never-ending task to ensure that we actually protect what is preserved.

That’s because setting aside half the earth for our fellow species is half of the solution. Actually protecting that land involves thinking differently about the other half. How do we house and transport people? Grow and provide healthy food? Create a just and meaningful economy? Mitigate climate disruption? Ensure clean air and water? Create ways to live sustainably? Plan cities that regenerate the way forests do?

The world is on track to build the equivalent of Manhattan every 35 days to accommodate the expected 10 billion people in 2100. China pours as much concrete in four years as the US did in the entire twentieth century. The challenges are both staggering and wonderful. There is so much scope for creatively rethinking how we operate.

In his 1984 book, Biophilia, E.O. Wilson posited that humans have evolved an innate love for life and the living process. But we have lost touch with it because we lack contact with nature. In Half-Earth he is calling for a shift in our moral reasoning. I agree, but, echoing Thomas Berry, I would instead say that we need a new story. Our morals arise from our stories.

The Western story, which has seeped into all corners of the earth, is one of ‘heroic’ conquest. Once by rulers and individuals, now largely by corporations and their political enablers. The wild world that we arose from, filled with our close kin, isn’t part of the story, except to celebrate mastery over it.

The cultural shift comes when, for example, we choose the living forest over the board feet of lumber it supplies. But the shift extends beyond loving the forest. It’s also in designing new ways to make everything from buildings to toilet paper to allow forests to live their full lives undisturbed.

That gorgeous birdsong thirty years ago told me that I belong to the larger order of beings. The birds whose voices we hear today have been singing in the dawn for 65 million years. Their passionate daily celebration reminded me I’m part of the continuing creative energies of the universe. Their loss taught me how fragile the fabric of life can be. Birds can disappear. Lots of species are disappearing.

But I find courage in the idea that Nature didn’t form us over eons with exquisite care and creativity so that we could turn around and destroy her. She is rising in us now, calling to each of us. Some can’t hear yet. But the many who can are adding their voices to the chorus, working to safeguard the nest.

~ RELATED POSTS ~

In 2008, Ecuador enshrined the rights of nature into its constitution, affirming that nature has the right to “exist, persist, and… regenerate its vital cycles, structure, functions and its evolutionary processes.” Where we stand on this profound shift may well depend on how we see the mountain pictured here.

WILD ABANDON: THE GLORY OF PLANT DIVERSITY

Standing on the rocky ledge that is Ring Mountain, with San Francisco in view, I’m surrounded by a staggering variety of life. This sheer exuberance is a wonderful mystery. Why so many forms, so many colors, so many variations?

GARDENING TO SAVE HALF THE EARTH

Activists focus on crucial projects like saving the vast Amazon basin. But it’s vitally important that we preserve, create, and connect local habitats everywhere we can. Mercifully, as gardeners, all we need is a shovel and the right plants to foster biodiversity where we are.

Thank you, again, Betsey. Good to publish this one again to remind us of the half-the-earth message of E.O. Wilson. Your quote from him in the introduction is perfect: . . . died two weeks ago today. His final inspiration was The Half Earth Project, a drive to save half the earth to protect the planet’s biodiversity. “I’m optimistic,” he said. “I think we can pass from conquerors to stewards.”

This “Saving Half the Earth” is beautiful, informative and inspiring. Thank you, Betsey!

Thank you, Van. More to come!

Interesant!

Merci!

I love your articles. I learn so much from them; they are so important.

Thank you for all of this.

Thank you so much, Nancy, for this wonderful, motivating comment!