The universe seldom operates in straight lines; certainly not for long, and only in details. A twig may be straight for an inch or so before hitting a node and angling off on another line. But the whole bush is likely to be a glorious circling of twigs, leaves, and flowers. Tree trunks can be beautifully tall and straight, but they radiate out into branches, twigs, leaves, needles. A flower stem may make a delicate line, but it, too, radiates leaves and ends with gatherings of round, tubular, or conical flowers, each creating its own center.

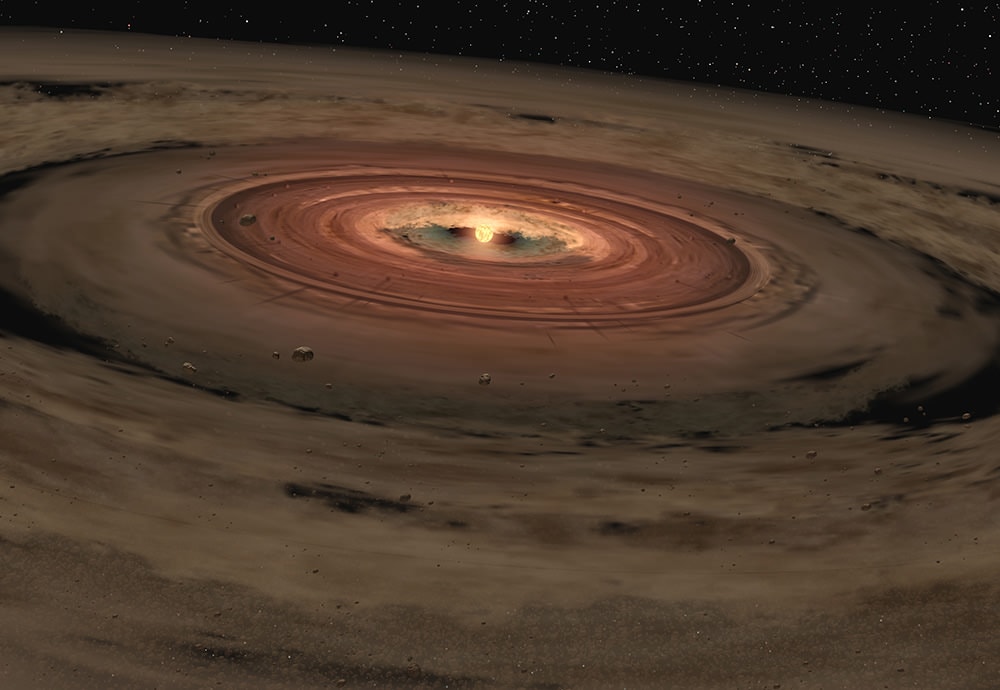

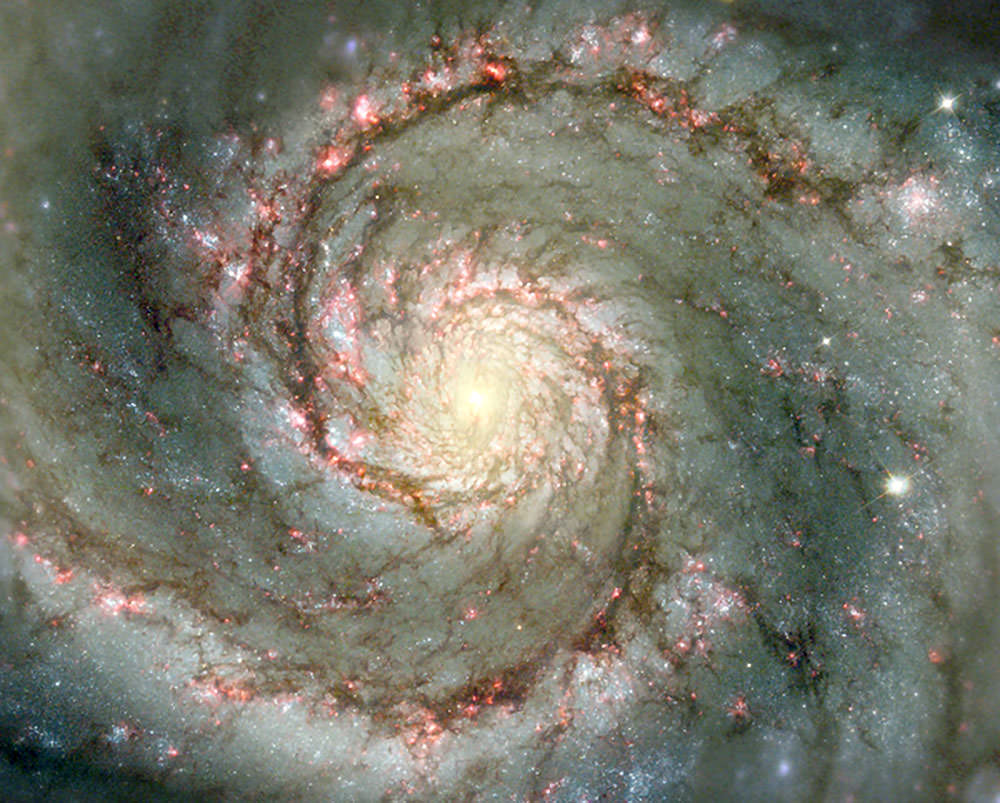

From birth, the cosmos has been turning in on itself, creating these centers: the early clustering of the original elements into stars. The swirling arms of galaxies gathering them together, then continuing to create more centers as new stars formed. The dust of the universe collecting itself into planets around those stars, and they, in turn, pulling matter into moons and rings. Centered planets within centered solar systems within centered galaxies. Without these gravitational formations, the earliest matter of the universe would have floated off into infinite space, and we would never have arrived and found a place to stand and contemplate it all.

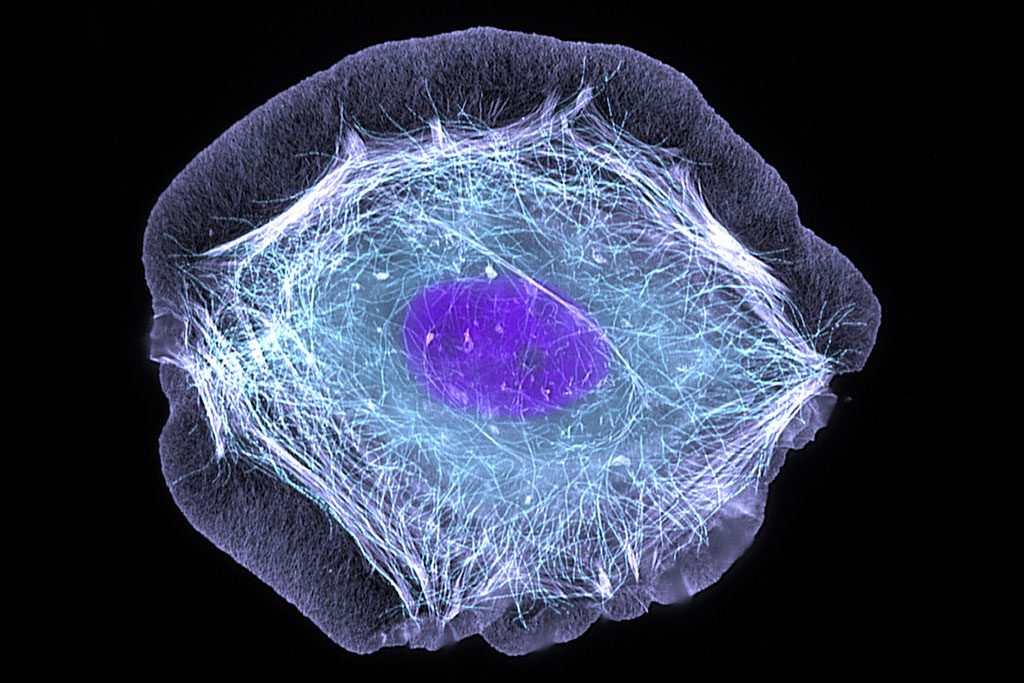

There are more: cells are centers, gathering together disparate working elements within an intelligent membrane. They then form into one nexus after another, getting more and more complex until conglomerations of centers — brains, lungs, stomachs — turn slowly into bacteria, algae, plants, fish, animals, birds, us. Water vapor gathers and falls as rain, or as snowy crystalline centers. The currents of the great waters flow in curves around the globe. The winds do the same, sometimes sweeping into great storms, with whirling water and wind, centers of great intensity.

In his series on the Powers of the Universe, cosmologist Brian Swimme calls this the power of centration. This is the second of my essays exploring what these great energies can teach us about how to move forward to the regenerative future we all desire. ‘The role of the human,’ Brian says, ‘is to enable the creative powers of the universe to proceed in a new and more mutually enhancing way.’ Even our desire for such a way forward, he feels, is a centering around the basic focus of animal life: to nurture ourselves and our young. We do this by gathering into families and communities. ‘The universe is aiming to bring forth…life that will carry life forward.’

Given nature’s minimal interest in lines, it’s intriguing that we humans have, unlike any other species, surrounded ourselves with them, creating a built world of squares and rectangles. This, Brian suggests, extends to our thinking about the entire cosmos: it’s ‘a box with a lot of things in it…and a lot happening.’ The society inside the box has ‘become like a machine, a vast network of interactions focused on its own perpetuation.’

One line that we’re particularly attached to is the idea of linear progress. We have created a culture in which our measurement of prosperity is that we create and get more and more. If the more is nutritious food, comfortable shelter, and useful education, then the gain is positive and potentially sustaining. If by more we mean tons of things in larger houses, more cars, vaster shopping centers, then the gain is going to overwhelm the planet. But this is the line we measure in the gold standard of progress: gross national product, or GDP.

This linear view of progress is insidious. Thinking that because we have more things we are better, more civilized, more advanced than those with fewer things fosters the idea that some people, species, places are worth less than others, and beyond that, expendable. This attitude underlies the idea that people living in poverty have done something to deserve their state, that species protection is incompatible with human endeavor, that the resources of the planet exist for our use.

I’ve been thinking about all of this because of an economist and firecracker-in-human-form named Kate Raworth, who has written a riveting and delicious book called Doughnut Economics. The shape of her economic model, with its circling double lines of permeable membranes, enfolding a well of conditions for human prosperity, is a perfect example of using the power of centration as we proceed into the 21st century.

In the ‘hole’ of the doughnut are twelve things that are required for a just and humane presence, living within the bounds of the planet, such as housing, equality, a role in politics, peace, health, food, and water. Falling into the center of this hole means we have a shortfall of these basic necessities. Outside of the doughnut is where we go into overshoot, using up the resources we have faster than they can be replenished, and discarding more than can be absorbed by air, water, or soil.

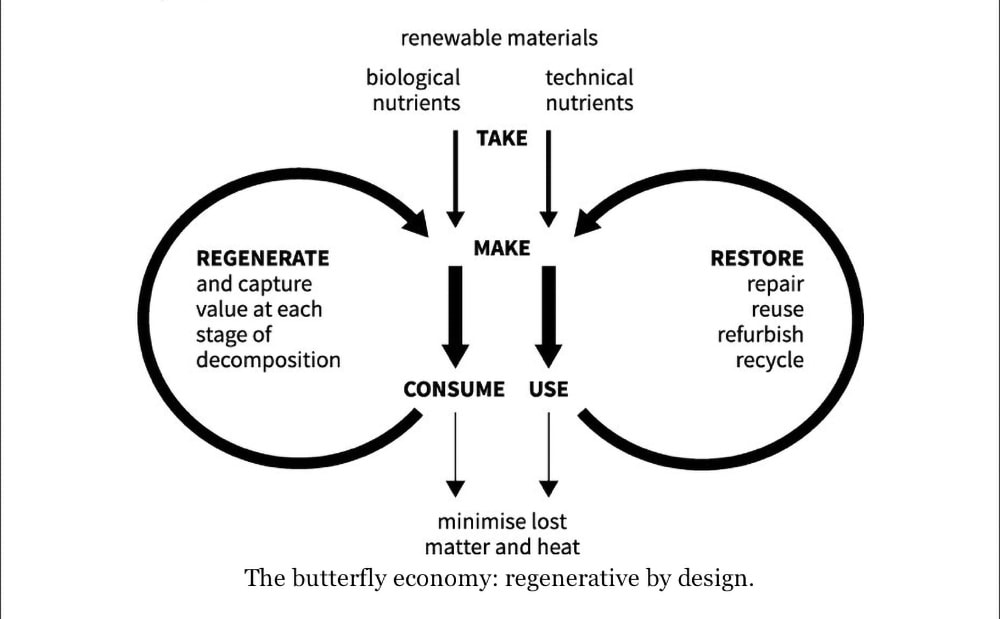

Though we’ve largely ignored it in the linear make-use-trash market we have today, the idea of a circular economy isn’t new. This is what Raworth calls the butterfly economy, a cradle to cradle model, where resources used to create goods are recycled back into the same goods, as with modular pieces, recycled into other goods, or repaired. Such ideas have been a touchstone of sustainable thinking for years and are excellent examples of using the power of centration.

But the doughnut is different. It’s not only an economic model, it’s a place. One where the planet can live comfortably and the thriving of our species doesn’t threaten the flourishing of any others. A circular economy is part of the doughnut, as is building a robust commons. Freeing intellectual rights from overuse of patents on knowledge collectively developed. Looking to nature to learn from its billions of years of experimentation and know-how. Creating cooperative businesses and endeavors. Understanding the utter interdependence of everything on earth. Designing equitable distribution and regeneration into the economy.

The “fundamental question,” Raworth writes, is “what enables human beings to thrive?” What will create “a world in which every person can lead their life with dignity, opportunity and community…within the means of our life-giving planet?” What allows for all humans to prosper, not just those blessed to be in situations that favor them, at the expense of those in less favored circumstances? And what is prosperity? Merely the accumulation of money and things? Or a world where everyone’s basic needs are met by design, not just a few by default?

Economic growth has proven to be effective for relieving deep poverty. But it’s based on the idea that we can just keep making things forever, with its concomitant mountains of garbage and overuse of earth’s supply of water, clean air, and resources. Even if we could keep this pace with a completely renewable, circular economy, recycling everything, leaving nothing to foul the earth, measuring our wellbeing by GDP “only values what is priced and only delivers to those who can pay.”

If you have asthma from a nearby toxic dump, every visit to the doctor counts toward the GDP and is thus included in ‘progress’. In our current economic thinking, there isn’t a usable measurement for no asthma and no toxic dump. Health and the ability to enjoy your neighborhood literally don’t count. By law, a corporation is responsible for maximizing profit for shareholders, not for creating and maintaining a living, prospering world.

Raworth points out that since the 1970s, the word consumer has replaced the word citizen, losing the far broader values, roles, and responsibilities the latter word invokes. The unpaid work that goes into our households, families, and neighborhoods — the foundations of our ability to thrive in the world — has no recognized worth. The doughnut changes this by “shifting our attention from merely tracking the flow of income to understanding the many distinct sources of wealth— natural, social, human, physical and financial— on which our well-being depends.”

This will require a radically different way of thinking, a different set of values. “Reversing consumerism’s financial and cultural dominance in public and private life is set to be one of the twenty-first century’s most gripping psychological dramas,” Raworth says. Even those of us who wish ardently to live within the means of the planet and want all beings to be able to blossom may well be thrown by the need to recalibrate what we cherish and desire. To decide what we’re willing to live without in order to live with our fellow creatures and the earth we share.

It will be a challenge in our culture, in particular, to subsume the modern version of the mythic rugged individual — the larger-than-life entrepreneur — into the need for communal centering. As Raworth notes, “Suddenly the words ‘neighbours’, ‘community members’, ‘community of nations’ and ‘global citizens’ seem incredibly precious for securing a safe and just economic future.”

The universe itself tells us that our current approach is unsustainable, and guides us forward. For all its long life it’s been gathering information about what works and moving past what doesn’t. It provides us with its incredibly flexible, generative energy, continually centering, gathering elements of itself for the creation of every new being or mode of being. This intelligent, vital force, Brian Swimme says, ‘has been roaring for 13.7 billion years and now it’s roaring into our lives. It’s been shaping the universe all this time, and it’s inviting us into the shaping itself.’

Both of my mentors here, while acknowledging the vast destruction we’ve wrought and how much work there is to do, are excited about our opportunities. Kate Raworth recognizes that a regenerative economy must be supported by regenerative economic design, which “is currently sorely missing. Making it happen calls for rebalancing the roles of the market, the commons and the state. It calls for redefining the purpose of business and the functions of finance.” But, she says, “taking on this redesign task is surely one of the most exciting opportunities for the twenty-first century.”

She sees many examples, worldwide, of a new, emerging paradigm. The power of centration tells us that these energies can be drawn together and strengthened into nurturing ways of living on and with our planet and our fellow beings. There is a great, sustaining joy in such a task, Brian says, in ‘feeling part of a greater self, rooted in energies that go back to the beginning of time…Feeling the partnership and participation.’ This exhilaration is ‘what the primordial energy of the universe feels like.’

I’d love to have you on the journey! If you add your email address, I’ll send you notices of new adventures.[madmimi id=178565]

Related posts:

reversing global warming

The doughnut is also the shape of the toroidal field around us humans and everything really (hurricanes, the planet itself) and the new free energy (for heat, power, etc) coming along.

Wonderful post, as always.

???

Fascinating! Love it all. Thank you!