Until man duplicates a blade of grass, nature can laugh at his so-called scientific knowledge.

~Thomas Edison~

Such a tiny word — poa, Greek for grass — to encompass one of the great life forces on earth. One of the most adaptive plant families, they’re the basis of human civilization. Every one of us is alive thanks to grass.

The Poaceae is the fifth most species-rich plant family on Earth. Over 11,000 different plants are spread out across every continent. They populate a quarter of the planet’s land. Half of the land in the United States is devoted to grass. Along with forests, they are among the most important stabilizers of both soil and climate.

And us. They’re the top source of nutrition worldwide. We may even have evolved into humans because of grass. Pollen fossils date back 70 million years. But it wasn’t until 5 to 8 million years ago that the vast grasslands we inherit formed.

During a period of cooler, drier climate, water-thirsty forests diminished, opening space for the adaptable grasses. The open landscape helped foster bipedalism among primates. Ultimately, that helped stimulate the development of our large brains.

Our hunter-gatherer forebears would have eaten the seeds of grasses along with other seeds, fruits, and tubers. Twelve thousand years ago, they started planting them. Though we can’t know what seeds the first farmers used, we know that all the ancient civilizations grew with grass.

Wheat, barley, and rye were grown in the Middle East. Rice, millet, and sorghum in China. Corn in Mesoamerica. Rice and sugarcane in India and Southeast Asia. Sorghum, millet, and tef in Africa.

Over the millennia, grasses have nourished humans and the animals we depend on. They have built, roofed, fenced, heated, and furnished our houses. Cleaned our air and water. Formed our soil. Made baskets, boats, and paper. They have cured diseases and powered our cars.

All this inspires the anthropocentric idea that humans have harnessed grasses to meet their needs and desires. But I like the counter take of some botanists: the plant has harnessed the human. What better way to ensure your survival?

Hook this clever species with the handy thumb and the ability to plan for the future. Provide enough nutrients to maneuver them into planting you everywhere they can, every single year for 12,000 years. Induce their browsing animals to open up more land for you to grow, all the while fertilizing your roots.

Convince them to plant 40 million acres of you around their houses. And then spend hours every week lovingly feeding and watering you while fending off pests. That’s power! I toyed with calling this essay “Our overlords.”

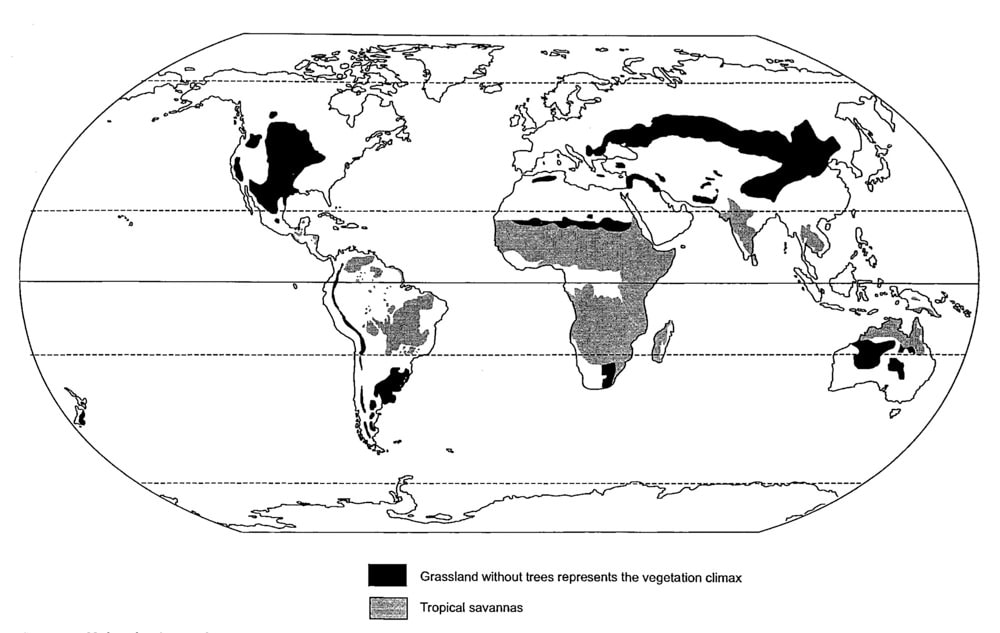

But that has negative connotations, and grass is a miracle. You don’t cover a quarter of a very varied planet without being a highly adaptable genius. In the US, we are most familiar with the prairie ecosystem of the Midwest. It’s vast, extending from the Gulf of Mexico north into Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

South America has similar systems in the Pampas and Llanos. Trees and grass combine to form the savannas of Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and the Cerrado in South America. The vast expanse of the Eurasian steppes extends from Eastern Europe well into China.

Grasses evolved several traits that would secure their eventual success. They are wind-pollinated, tossing their pollen into the air. The wind spreads it far and wide, creating a lot of opportunities for pollination over a large area.

They form deep roots, up to five times the height of the plant. This vast ecosystem supplies their needs for water, nutrients, and stabilization. And not just for themselves, but for the soil they, and the rest of us, depend on.

Crucially, they developed a key variant in the photosynthetic pathway. C4 photosynthesis allows for more efficient use of sunlight and water in creating carbohydrates. With this skill, grasses use less water, grow in nutrient-poor soils, and allocate more of their biomass to roots.

C4 plants are very efficient at pulling in carbon dioxide and sequestering it in their miles of roots. This gives grassland preservation a pivotal role in climate stabilization.

They are also imperative for preserving biodiversity. Grasslands are not only grass. They form a matrix for many other plants that grow with them. On one of its restored prairies, the Missouri Prairie Foundation found 46 separate native plant species in a 20 by 20 inch plot.

They provide food and habitat for countless beings that are part of the web of life. Birds, bees, butterflies, mammals, reptiles, microbes, fungi, and others. They have co-evolved with some of the most majestic life forms on the planet: buffalo, gazelle, zebra, giraffe, elephant.

Grasses depend both on these beings and domestic grazers to keep land open for them. But they have ways of protecting themselves from overgrazing. Various toxic phenols and alkaloids, including cyanide, increase as grazing pressure rises. Phytoliths, minute shards of silica, wear grazers’ teeth down.

Budding crowns kept just under the soil prevent nibbling muzzles from damaging them. As the grazers clean off the upper stalks, new shoots have ample air and light to grow. In the meantime, grazers deposit fertilizer and move on, allowing grasses time to recover.

Some of the most diverse places on the planet are grasslands. But we have tended to treat them as wasted space waiting for us to make them productive. Thus, 99% of the American prairie has been plowed, planted, developed. The South American Cerrado is headed in the same direction.

Using large open areas for agriculture makes sense. But the current state of monoculture farming is damaging. Yearly tilling to plant single-species annuals with shallow roots. Using high nitrogen fertilizers along with artificial pesticides and herbicides. Such practices ruin the important gifts of grasslands. Soil erosion is high; biodiversity and carbon sequestration are low to nonexistent.

I love the subtle beauty of grasses with their feathery flowers and am deeply moved by grasslands. I’m not sure where this came from, since I grew up in suburban New York. But one of the most moving experiences of my life was standing in a grassland in South Dakota. I was driving back roads north along the Missouri River. One stretch took me into the shortgrass prairie of that dry area.

I was up to my knees in sun-filled grasses, flowing like golden water with the wind. It was so hot the air itself was an intense presence. Despite the wind, there was utter quiet. Everything else fell away into nothingness. At that moment, swept into the warm, moving air, I was grass.

As we all are. We share up to half of our genes with grass, a legacy from common ancestors. Sixty percent of human caloric consumption worldwide is grass-based. We are literally grass. We are formed by it, and we are inextricably bound into a miraculous matrix of interdependence.

To see this clearly is to plant ourselves into the very roots of life. It means we live on Earth not as users but as participants, surrounded by equally important partners. We can then hear their message. The skill grass chose us for — our ability to plan for the future — is being called forth to help all of us prosper on our mutual planet.

~ RELATED POSTS ~

THE GEOGRAPHY OF HOPE:

SAVING HALF THE EARTH

Biologist E.O. Wilson had a radical proposal: save half the earth to preserve biodiversity. Simple. And complicated. The challenges invite us to think about the other half.

LIVING LIGHT: THE CRUCIAL MIRACLE OF PHOTOSYNTHESIS

To love plants is to be in awe of photosynthesis. A crucial, we-wouldn’t-be-here-without-it miracle. Its ramifications are so vast that once it showed up, it dictated all of the evolution that followed.

PARCELS OF PRAIRIE: THE PAWNEE NATIONAL GRASSLANDS

A short grass prairie never suitable for farming, the Pawnee Grasslands were born out of grief. Now they are filled with quiet beauty, dramatic skies, hundreds of birds and other wildlife, and enough wildflowers to make me very happy.

Tweeting! xoxoxoxo

Thank you for your amazing insights! As I read what you wrote I felt a wave of connection to everything. From a blade of grass to tallest redwood, everything serves a purpose in the great scheme of life on this planet .