I live on a small mountain next to a larger one. Both are modest as mountains go, but at 2600 feet Mount Tamalpais reigns over the area like the queen she is. My apartment is on one of her foothills. If I walk up a steep fire road for a quarter of a mile, I arrive at the two-mile King Mountain Loop.

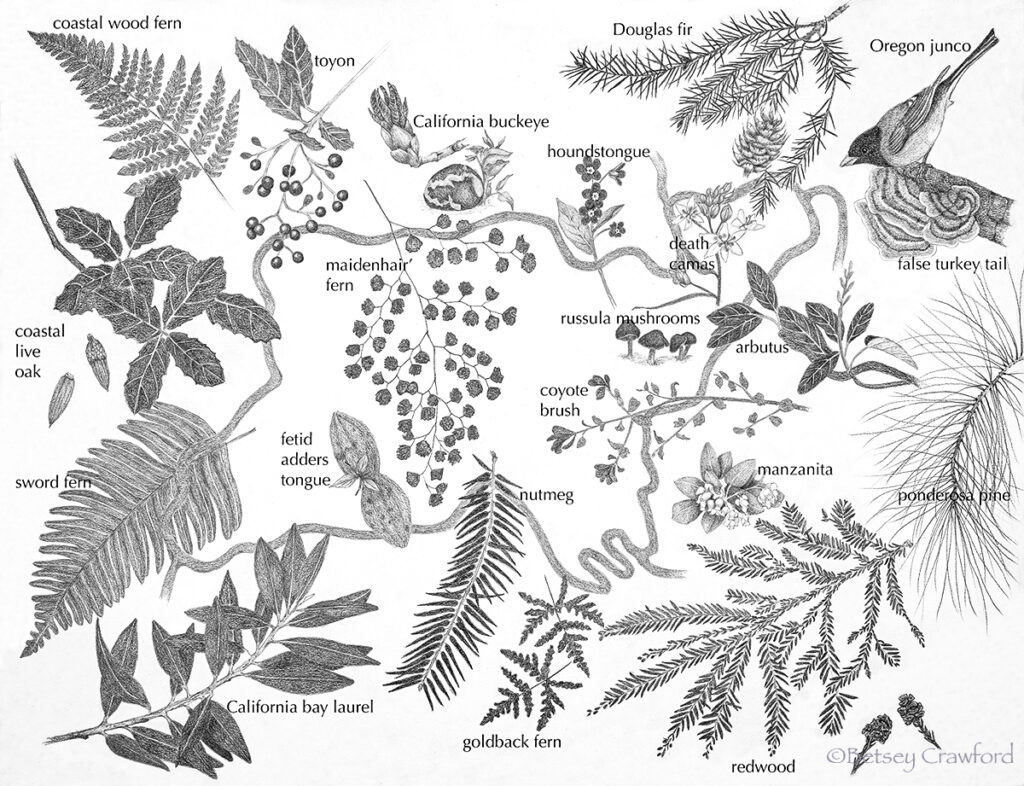

It’s all forest, a third of it redwood forest, the rest a combination. Most of the trees in my neck of the woods are evergreens. So here, nature in winter is green. There are needled trees: redwoods, nutmegs, and Douglas firs. There are leafy ones: coast live oak, tanoak, and California bay laurel. The one deciduous tree on the loop is California buckeye, which leafs out in February.

Under their canopies, life abounds. There are lots of evergreen shrubs: coffee berry, coyote brush, toyon with its bright red winter berries. Under those are flowers, animals, fungi, lichen, moss, ferns. Last season’s seeds start sprouting in the middle of our mild coastal winters.

I consider it my backyard hike. I enter it at the lower left-hand corner of the drawing at the top. The mountain continues to climb upward inside the loop, and tumbles downhill on the outside, sometimes dramatically. I did the drawing over two winters, celebrating the life I find along the loop.

In this part of the world, we have meteorological winter, which goes from December 1 to February 28. In our Mediterranean climate, this usually means rain. Light rain, heavy rain, intermittent rain, atmospheric rivers, drizzle, wispy fog, fog so thick it’s feels like it’s drizzling. If it doesn’t rain, and some years it’s sparse, that means drought because come April, rain isn’t due until October.

So we love our rain, no matter how hard and long it falls. It can rain for days, so I try to get out in between bouts. An app gives me the rain forecast for the next four hours. I use it but if it’s a stormy day, I wear rain gear. Too often those are precisely the four hours when it rains. Once it hailed.

My favorite gifts of rain on King Mountain are the waterfalls, eight or nine of them. Whenever I try a count, I forget at some point on the loop and miss at least one. They are all small. Water tumbles down the hillside, falling over rocks, flows across the trail, and continues downhill. After a rain, you walk in and out of the sound of rushing water.

Stormy days litter trails with leaves, twigs, branches, sometimes the whole top half of a tree. Or an entire tree. Trees have shallow, spread-out roots to capture water and nutrients from decaying detritus on the forest floor. Given a sodden ground, especially with a strong wind, some trees will topple. As they fall, they lift a wide circle of roots right out of the ground.

So, though the loop is fairly easy, winter hikes can include stepping around, bending under, or climbing over such obstacles. A wide oak tree went down one winter and covered thirty feet of the trail with a wild tangle of branches.

Undaunted, hikers immediately made a wobbly trail on the slope below. Tricky to navigate because with every step you could slide further downhill. In time, the county came and cut the branches, piling them in a thicket near the trail.

Leaving them creates habitat for birds and small mammals. Insects move in and start the work of breaking the wood down, The bugs, in turn, provide food for birds. Moss, lichen, and fungi of various kinds take over.

It’s never easy to see a tree fall. But spending time in the woods shows you that decaying trees are a hotbed of life. All the way to the end, when entire process has slowly formed the rich soil all other growing things depend on.

Over time, that soil has filled the loop with ferns. I included four different ferns in the drawing at the top, and left out at least one. They range in size from the three foot long fronds of sword fern to the two inch long goldback ferns. The latter dry up once the rain stops in the spring, looking shriveled and dead. It’s a sign of the coming winter when they unfurl as rain returns in the fall.

My favorites are maidenhair ferns, with their delicate lines of black stems and soft, rounded green leaves. They cascade down the shady sloping cuts that line large sections of the trail. I never notice them disappearing, but all winter more and more of them show up.

The older fronds of sword and wood fern don’t seem to disappear, either. The oldest turn brown and eventually detach. But plenty of younger fronds stay green. Towards the end of winter, the fiddleheads begin to show up, unfurling into ever brighter green through spring and summer.

Moss and lichen don’t shrivel up in the dry season, but they are in their glory in winter. Lichens plump up and uncurl. Moss turns vivid emerald green, becomes soft and fluffy, ready to reproduce and spread.

They both thrive on living trees and dead ones, on rocks and bare ground, branches and twigs. Both are slowly creating soil and enriching the life around them. Plenty of flowers grow out of moss patches, plenty of insects live in them. Birds use moss for nesting.

Except for that nesting time, the King Mountain birds don’t tend toward lovely songs. Spotted towhees give occasional squawks, usually in the same neighborhood. They have claimed a nice, open section, nesting in large shrubs well below the trail. Even more occasionally, a jay will object to something, also a squawk but in a lower pitch.

Though I never see them, I hear the hooting of great horned owls in winter since they breed in January. Sometimes a screech owl joins in. The tapping of hairy woodpeckers and northern flickers is, surprisingly for a forest, less common than their not very melodious call. But they, too, are occasional.

The three birds I spend the most time with during King Mountain winters are crows, ravens, and juncos. The crows and ravens come and go, usually hanging out together, always in the air, often making an amazing amount of noise. Party birds, an ornithologist friend calls them.

One New Year’s day, a large flock wheeled and cawed at each other for hours, the ravens’ voices deeper than the crows. I like their cheeky brilliance, but their presence is a sad sign that songbirds have largely abandoned the area.

Small, black-hooded juncos are a constant presence. I doubt I’ve ever walked there without seeing them, often in small bands. Their song is mostly reserved for spring nesting and mating. The rest of the year, they make little chirps as they flit about.

Staying close to the ground, their frequent lift off and landing gives the impression they’re bouncing around. My presence doesn’t seem to alarm them, though they go into bushes when I get close.

Squirrels chitter and scold in the branches, sometimes holding forth for a long time, as if delivering a lecture about forest behavior. Deer I haven’t seen suddenly move as I come near, startling me at the same time I am startling them.

One evening a big, large-antlered buck blocked the trail, standing still for a long time. I did, too, both of us eying one another, wondering what each had in mind. He eventually moved off and climbed the upper hill with his mate.

Coyotes live on the mountain. I can hear a pack of them yipping occasionally from my apartment. But I’ve only seen one, crossing the trail ahead of me at twilight. Disappearing tail last into the underbrush as he continued downhill.

On a recent walk, twilight too quickly turned dark as I hiked and a pack started their haunting calls. They were farther up the hill, but that’s not far. I love being out late in the day, into the evening. But both times had me pondering the wisdom of being in the woods, in the dark, at my age, with a pack of coyotes.

When I first started hiking the loop, a few years before I lived next to it, it was to look for wildflowers. And they are abundant, starting in winter. Among the earliest are the shrubby, soft green manzanitas with tiny, white, inverted-bell flowers. Along with them, the bay laurel trees open their even tinier yellow flowers clustered at the tips of their branches.

My first winter here, the vivid blue houndstongues bloomed by December 28. I knew I’d moved to the right place. They haven’t bloomed that early since, but their purple stems and silver-green new leaves start to break ground by then. They are the first of the perennials, and, being blue, among the rarest flowers. For the last three years, a patch of pure white sports has bloomed.

Milkmaids follow houndstongue. White, occasionally pink flowers so delicate they look incongruous among the twiggy chaos of the forest floor. Both last a long time, the milkmaids well into spring.

Fetid adder’s tongue is more fleeting than its companions. First the leaves, green mottled with purple, the buds rising from the center on single stems. Then, displaying an interesting combination of dainty and gothic, the purple-striped flower opens up. It’s the wildest flower imaginable, but tiny. Without the distinctive leaves, the flowers would disappear in the mix of decaying fern and redwood tips on the ground.

The shift into spring is happening as I write this. Death camas, so named because it’s poisonous for grazers, is a sign of the season turning. Their buds, too, are rather gothic, swelling in their green cages during February and then blooming from the bottom up as the month turns into March. As if giving a signal, several other wildflowers follow suit and begin the cascade of spring bloom.

If I need further proof the season is changing, it’s my nose that discovers it. The open section favored by towhees is the sunniest place on the loop. It’s the only place where California sage grows, adding fresh growth as winter wanes.

Just about now, its complex, aromatic spiciness greets me as I pass by. It’s not a smell of winter, if there is one. It’s a sultry, sensuous scent, speaking of hot, sunny weather, of dryness. Of the months to come, not the months that have just passed.

I love that scent, but it comes with poignance. I don’t look forward to the wet chilliness of winter, but once it’s here and I’ve settled in, I find it hard to let it go. I feel the rising excitement of spring with the riot of bloom and birdsong that comes with it. But the quiet and subtlety of nature in winter is deeply appealing, especially in these difficult days.

Yet, as is common with spells of quiet, a lot happens, above ground and below, inner life and outer. Life’s creative forces are never still. There are always gifts of beauty and curiosity, new life and old, wonder and mystery. Showers of blessings that mend our souls and nourish our energies to protect the world we cherish, the beings we live among.

~ RELATED POSTS ~

STALKING THE ELUSIVE ADDER’S TONGUE

The first year, seeing the leaves sprinkled through the redwood forest, I suspected I’d one day see a flower. It took a few years of looking before the delight of my first one. And then, as so often happens with quests, the end was only the beginning of the gifts.

FERNS: THE DEEP CONSOLATIONS OF SURVIVAL

Ferns are a hardy bunch. We would be, too, if we had survived for 360 million years, outlasting two major extinctions, feeding dinosaurs along the way. Their ancient lineage gives our own existence depth to depend on. Plus — a big surprise.

When my partner George died in autumn, I dreaded the coming rainy season, fearing only darkness and storms ahead. But one soft, misty January day, walking a trail along the edge of a mountain, I realized how wrong my foreboding had been.

I LOVE the drawing!

I don’t know how you make ferns and lichen thrilling, but you honestly do. It’s the “noticing,” as someone we both loved would always say – and your elegant, graceful, and intensely-observant prose. (And, of course, there are the drawings and photographs…)

I could feel the darkness falling, hear the water tumbling over the hillside rocks, sense the chill in the air as winter arrived… Magical stuff; always there, too often overlooked by so many of us. MLAA

What a lovely comment! Thank you so much.

This is so beautiful, Betsey!! What an amazing life you have created in an amazing place. Your writing, photographs, art, and perspective are deeply uplifting. I LOVE your drawing!!! It’s glorious. I hope you make a huge print of it and hang it in your apartment. Thank you for sharing your journey. 💛✨🙏

Thank you so much! It is an amazing place. But so many are! Love to you.

Beautiful! Thank you for taking us on your hike with you and experiencing all the amazing thrills. 🤩💚

Thank you! It is thrilling to live among all these small miracles.