Vision is an art, and nature an old master painter teaching us how to see the underlying reality of things to be — before they actually are.

~ Monica Gagliano ~

In 1977, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City had a major exhibit of Paul Cezanne’s paintings. On my first visit, I took one look at the around-the-block waiting crowd and became a member. I could then skip the lines and come as often as I wanted. I was twenty-six then, painting every afternoon at the Art Students League several blocks away. A few days a week for three months, I would stop at the museum on my way to the League and spend time with Cezanne.

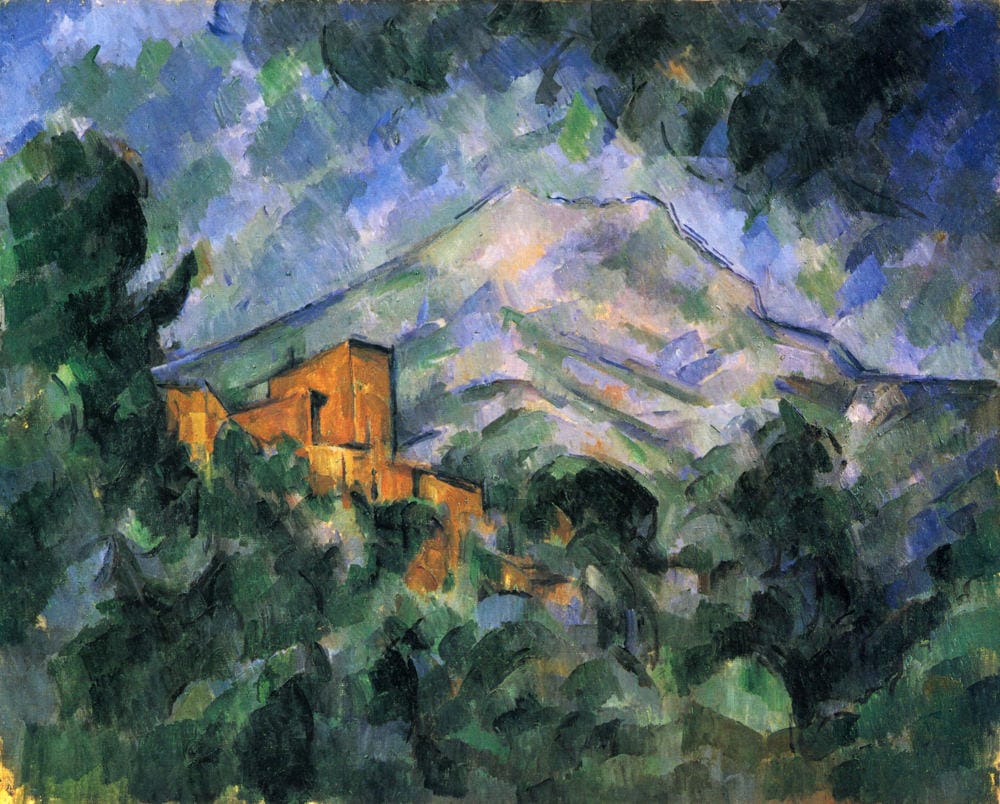

It didn’t matter how crowded the galleries were. I’d find an open spot and enjoy whatever painting was there. I was especially interested in the landscapes. In particular, his renderings of Mont Sainte Victoire near his home in Aix-en-Provence. The Impressionists are celebrated for their breaking up of light and color, rendering surfaces as complex and luminous.

Cezanne, leading the way into Post-Impressionism, painted the mountain as innumerable facets of color and light. At the same time, he grounded his subjects, giving them heft and weight even as he dissolved their surfaces. So Mont Sainte Victoire was both solid rock and innumerable small plates of shimmering light. It wasn’t until many years later that it occurred to me that Cezanne’s vision paved the way for my time with shamans. Art frequently shows us things we can’t yet think.

My shaman experience started with the wildest thing that ever happened to me: hawks started showing up in my life. I was in my mid-fifties, living a life full of normal things: family, home, work in my landscape design business. It was full, too, of complexity. I was mothering through the rocky shoals of adolescence. My father needed increasing care in his last years. I was burning out.

Then hawks started landing on my patio, on the deck, on the ground outside the windows. One flew in front of the windshield as I drove, another across the headlights one night. One crashed into my bedroom window. They waited on trees on hikes and didn’t fly away as I got near. By the time this stopped a year later, there were well over a hundred of these magical visits.

I was utterly mystified. What are they telling you? a friend asked. I had no clue. I was fine with the idea that hawks would communicate with shamans and medicine people. But I couldn’t imagine what they would say to me as I trudged daily through my to-do list. I asked a friend who leads vision quests if she knew someone who could explain what was going on.

She introduced me to Val, a shaman in the Andean Quechua tradition, and the nearest to a tornado-in-human-form that I’ve ever come across. The next thing I knew, I was at the first of a gathering of her students. I went with the attitude one would take to an unfamiliar religious service: curious, open, willing to participate.

Val had told me that lots of people were having experiences similar to mine. And so it seemed. Hawks were a normal thing to this gang. “Oh, right, hawks. I’ve seen one every day since I held one in a raptor rehab center.” This was, though unique in itself, a fairly standard reaction. One woman offered to send me feathers, which she did. Another had so many animals showing up in her life that her husband, coming home one day, stepped over a snake on the front porch. “One of your friends is at the door,” he told her.

We gathered twice a year for five years. By the time we finished, everything in my life had changed. Having already started on the journey I began in 2011, I came back for the last two gatherings. But things started changing after the first weekend.

This essay is not about that wondrous path. Instead, it’s about one reason things changed so dramatically. In my experience, shamanism, like Cezanne, breaks the surface of the world into luminous, shimmering energies. And I was ready to be borne along by them because Cezanne had already painted the possibility.

I made this connection a few years ago, and it came back to me recently while reading Thus Spoke the Plant. Monica Gagliano is one of a group of revolutionary plant scientists I mentioned in my essay about ferns. And she is very revolutionary. It wasn’t hawks for her. The plants themselves were calling. She went straight to the heart of the call and flew to Peru from Australia to meet a shaman who had appeared in a dream. He guided her through her first dieta, a process of isolation, fasting, and ingesting decoctions made from selected plants.

Amazonian tradition holds that the plant world is full of teachers. As they have done for shamans and medicine people for millennia, the rituals opened a powerful connection to the plants themselves. Through their guidance and even direct instruction, Gagliano created several rigorous scientific experiments that showed that plants can learn, remember, and respond to sound.

As described in her book, her experiences with plant medicine are riveting, the experiments they led to groundbreaking, her insights profound. Their reception was troubling. Her colleagues, who then knew only the scientific breakthroughs and not the spiritual ones, stopped speaking to her when they passed in the hallways. “As if I were infected,” she says. They lobbied the administration to forbid her from teaching undergraduates, so she wouldn’t ‘infect’ them.

In 1894, physicist Albert Michelson acknowledged that “it is never safe to affirm that the future of Physical Science has no marvels in store even more astonishing than those of the past.” Nevertheless, he was confident that what lay ahead was the refinement and application of laws already discovered. Six years later, Max Planck defined the quantum, the basis for quantum physics. Eleven years later, Albert Einstein published his first paper on the theory of relativity. Nothing in physics was ever the same again.

Few would echo Michelson now. Despite the lure of a Theory of Everything, each discovery keeps leading us to more mysteries. We have no idea not only what we don’t know, but what we can’t know. We can only find what we are capable of looking for and at. What would we be able to encompass if we weren’t limited to the five senses we have? For our descendants several evolutionary leaps from now, communicating with plants may be as commonplace as seeing color is for us.

We don’t have to wait. There are Indigenous people who routinely communicate with plants now, but, as with my hawk visits, our Western cultural mindset doesn’t accept it as possible. Thus, we have plant scientists so threatened that they stop talking to a friendly and ebullient coworker. Simply because her unexceptionable data brings them into territory that doesn’t match their view of the plant world. This isn’t a new phenomenon; human history is full to the brim with people resistant to new ideas.

Copernicus’ discovery that the earth orbits the sun instead of vice versa took 200 years to take hold. Right now, 100 years into quantum mechanics, most of us will look at our hand and see a solid Newtonian mass of particles. We may never see the moving waves of probability reverberating in mostly empty space that it actually is. Even Einstein could never accept the premises of quantum physics, though he loved talking to other physicists about them. Cezanne and his fellow artists remained anathema to the powerful, traditional Salon de Paris for decades.

The hostile pushback may be one reason we choose to take no steps at all. In the fern essay, I wrote about the late nineteenth-century botanists who discovered ocular cells in plants that could even be used as lenses for photographs. No one took up those ideas for 100 years, although the twentieth century included breathtaking advances in every field of thought.

This makes me wonder if there’s something in our attitude to plants that prevents us from encompassing their broader reality. We treasure them. We wouldn’t be here without them. They are crucial and adept partners in human life as food, shelter, medicine, pleasure.

Yet there is such resistance to ascribing intelligence to them that scientists shun their colleagues when they get out of their comfort zone. As someone who has loved plants since early childhood and has centered my life around them, I find this mystifying.

Acknowledging intelligence in beings that have been thriving for 500 million years seems a given to me. Adaptability is intelligence. So is the ability to make choices, communicate, create relationships, remember, evolve. They don’t have the same neural intelligence we have. But the oldest homo sapiens fossils are only 300,000 years old and we’re already wondering if our actions are inviting our extinction. Not a great advertisement for our version of intelligence.

The resistance is disheartening. If we are going to solve the problems facing us, we need to break open the surface of our knowledge and habits and see the radiant possibilities and pathways beyond. We can’t shun the people leading the way because they bring us news we aren’t used to.

Our questions need to lead us deeper into the mysteries, not running for known territory. In talking to other scientists studying things like amoebas and slime molds, Gagliano has found nothing but expanding wonder. “These critters are amazing. They do stuff that we don’t even dream of. And by not dreaming of it, we assume that it does not exist.”

If the dreaming earth had stopped at amoebas and slime molds, we would not be here to contemplate all of this. Instead, all the generative powers governing our planet have led to one marvel after another since life first sparked into existence four billion years ago. By limiting our dreams to what we already know, or can easily comprehend, or feel safe with, we cut off boundless possibilities.

Instead, we could allow our perceptions to become fluid, to see luminous, shimmering energies everywhere. By inviting them to teach us the treasures they bring to life, we reenter the dream of the earth we emerged from. Blending our gifts of imagination and resourcefulness with that supremely creative force.

(Top: Mont Sainte Victoire (1890) Private collection.)

~ RELATED POSTS ~

We live a life of supreme interdependence with seeds. Our presence on the planet depends on them; our intelligence has evolved with them. They are mighty packages of fierce and beautiful energy, full of deep wisdom that know when, where, and how to spring fully to life.

BEAUTIFUL VAMPIRES: THE CASTILLEJA GENUS

Gorgeous parasites, the Castilleja genus is both radiant and smart, with roots that read their neighbor’s presence, and head over to borrow nutrients. They bring up a fascinating question: what do plants know?

Every few years Alaskan spruce trees produce an overabundance of cones to keep ahead of voracious red squirrels. How does a spruce tree ‘know’ that doing this means they can ensure enough offspring without spending the same energy every year?

What a fine decision I made this morning~~~In the past when I saw your offering, I briefly opened it, then passed it by and eventually deleted it along with too many busy, intruding pieces of distraction. In spite of my “lists” of “necessary-must-dos” I was guided this morning to not only look at your gift but I also began to read with attention, gratitude, and internal smiles of warmth and connection. Thank goodness I did. Thank you Betsey.

Thank you, Judi! So glad you connected.

This is my fav of your posts so far. So deep and insightful. I’m sure the Earth thanks you for putting words to her feelings and wisdom. And—I remember that Cezanne exhibit very well (age 16).

Thank you, Annie. I love the way you put this.

I love how you pull so many threads together, Betsey, creating beauty, perspective and deep connectedness.

Thanks so much, Hele. I do love pulling threads together. And discovering how they are all connected somewhere.

Thanks for another stunning, insightful, and beautiful set of interconnected realities, Betsey! Your images and essays never disappoint! It’s a long time since I read it, but you might like Art and Physics. It shows that what our artistic selves intuit often precede scientific discoveries related to it. Cezanne might be in there! (I’m not listing my web site because I no longer add to it.)

Thank you for the reminder, Terri, and the lovely comment. I remember wanting to read Art and Physics and then forgot about it. It’s already ordered!

Thanks for another inspired essay Betsey! Love the Cezzane pieces sprinkled throughout. This has really brightened my day!

Thanks so much, Marianne. I had a great time looking for the Cezanne pieces to include.

Betsey, thank you for sharing. What a marvelous experience you have had with hawks! I’m curious if you still have run ins from time to time or happened to dream of them? This was a wonderful post, your reverence for the natural world is beautiful and inspiring. I too wonder about what magic and power the the plant kingdom holds, the untapped knowledge, medicine, and connection waiting patiently for us to blossom.

I always was taken by the fluidity of Impressionism, specifically the way post-impressionists seem to encompass the breath into their work. As if the painting was rising and falling with my own.

What a treat to see such artworks at a young age, I would love to hear more about your years in New York.

Lauren

Thank you for this beautiful comment, Lauren. I love this line: “I too wonder about what magic and power the the plant kingdom holds, the untapped knowledge, medicine, and connection waiting patiently for us to blossom.” And yes, growing up near New York City meant access to incredible art from an early age.

Betsey, this is a marvelous thought-provoking essay. Yes, we look to science for some kind of truth, but when many if not most scientists are unable/unwilling to open their minds to new discoveries, everyone is handicapped. Instead, many of us are rediscovering the reality of deep sensitivities and subtleties of Nature that all Indigenous people have always known, especially regarding trees and other plants. And I LOVE the Cezanne paintings! Thank you so much for introducing me to them!

Caitlin

ps: invitation still stands for you to stay with us in Vermont

pps: My husband just wrote an essay that you will enjoy, called “The Wonder of It All”. I will send it to you.,

Thank you, Caitlin. You wonder why some scientists are in the field if they’re resistant to new ways of looking at the world. I have your invitation in mind! And look forward to the essay.

Thanks, all this is so good, I felt a call from nature to look closely to all that is around no matter how shuttle.

Everything we see is a relationship, to the center of our core.

Easter peace be yours, Grace

Thank you, Grace. I love what you say here, especially “Everything we see is a relationship, to the center of our core.” Lovely!

This is so exciting! And thrilling. I immediately thought I’d better water my (very few) “houseplants” right away. And then even the word “houseplants” seemed to be an expression of ignorance on my human part – a failure to understand who I really have sitting in those pots where I have imprisoned them.

And those are the MOST luminous and wonderful Cezanne images I’ve ever seen…

LOVE THIS POST! (And she who posts…)